The “Francesco Ribezzo” Archaeological Museum and the Treasures of Brindisi

Ithaca

If you set out on your journey to Ithaca,

pray that the road is long,

full of knowledge and adventure.

Do not fear the Laestrygonians or the Cyclopes

or angry Poseidon:

you will not encounter any of these along the way

if your thoughts remain lofty,

if a noble emotion touches your soul and body.

You will not meet the Laestrygonians, the Cyclopes,

or the fierce Poseidon,

unless you carry them within you,

unless your own heart sets them before you.

Pray that the road is long.

That there are many summer mornings

when, with great pleasure and joy,

you enter harbours seen for the first time.

Pause at Phoenician trading stations

to acquire fine goods,

mother-of-pearl, coral, amber, ebony,

and sensuous perfumes of all kinds—

the most abundant you can find.

Visit many Egyptian cities,

to learn, to learn from their scholars.

Always keep Ithaca in mind.

Your destination is to arrive there.

But do not hurry your journey.

Better that it lasts many years;

and that, as an old man, you anchor at the island,

rich with all you have gained along the way,

not expecting Ithaca to make you wealthy.

Ithaca has given you the beautiful voyage.

Without her, you would never have set out.

She has nothing more to give you.

And if you find her poor, Ithaca has not deceived you.

You will have become wise, full of experience,

and will understand by then what Ithaca means.

Ithaca and the Philosophy of the Journey

The Greek-Alexandrian poet Constantine Cavafy, writing in the early 20th century, portrays the journey to Ithaca as a metaphor for life itself. He wishes the traveller a long road, full of unexplored treasures and distant wonders—or terrifying, monstrous creatures. Cavafy encourages the hero to get lost like Odysseus, to divert their focus from the destination, to revel in the voyage, and to let fate’s currents guide them. Ithaca becomes a symbol of wisdom, attainable only through suffering. This concept has deep Greek roots, originating in Aeschylus’s phrase pathei mathos (πάθει μάθος, “learning through suffering”). Pain, according to this view, is humanity’s sole means of gaining knowledge.

The same blend of fearful curiosity and suffering characterises the journey of the earliest peoples who reached the shores of Puglia. It was a bold leap into the unknown, a plunge into an unfathomable sea.

The Greek Sea and Its Many Names

The Greek sea bears many names. The most widespread is Thalassa/Thalatta, but its etymology remains a mystery, with no clear Indo-European roots. Albin Lesky observed that the most common Greek word for the sea isn’t Greek in origin. This suggests that the Greeks living in continental Europe had to ask the indigenous peoples of the Aegean shores to name that mysterious, fearsome expanse of saltwater.

Before Jason and his quest for the Golden Fleece, humanity clung steadfastly to the land, unwilling to risk its life on the open sea. Crossing the waves marked the end of humankind’s primal innocence. Seneca, the Roman poet and philosopher who lived under Nero during the empire’s maritime expansion, wrote:

“Bold indeed was he who first entrusted his fragile craft to the treacherous waves,

who left the land behind and surrendered his life to the caprice of the winds,

who sailed the open sea on an uncertain course, trusting in a fragile plank,

a thin line between life’s paths and death’s abyss.”

The Mythical Seas of Antiquity

The voyage of the first sailors must have seemed even more monumental when considering that, in ancient times, the river Oceanus (Ὠκεανός) was also believed to be the realm of Hades. The sea, with its ominous wine-dark hue at sunset (as Homer described it), evoked dread, a sense that its depths held unearthly dangers. Its colour, its endless horizons, and the many shipwrecks it claimed made it a symbol of death and the afterlife in the ancient world.

Greek curiosity, however, proved stronger than fear. Behind each island lay new waters, and the search for the “final island,” the farthest land, was inevitable. This pursuit of the ultimate boundary inspired the myths of Aia/Aiaia, the land lying at the utmost edge of the world.

Ancient Explorers and Puglia

Herodotus recounts that the Cretans, led by King Minos, sailed to Sicily to besiege the mythical city of Camicus. A storm, however, drove them ashore in the land known as Iapygia (modern-day Puglia). Stranded, their ships destroyed, they decided to stay, founding the city of Yria. Other sources suggest that the Iapygians were indigenous to Puglia or were descendants of Cretans who arrived with Theseus, the mythical founder of Brindisi. The Roman historian Varro proposed a triple origin for the Iapygians: Cretan, Illyrian, and local.

The “Francesco Ribezzo” Archaeological Museum | Overview

Situated in Piazza Duomo, the Francesco Ribezzo Provincial Archaeological Museum chronicles Brindisi’s history from prehistory to Roman conquest. Noteworthy exhibits include Attic vases, the Bronzes of Punta del Serrone (discovered through underwater archaeology), and the striking Templar Portico, which houses anchors, sculptures, and sarcophagi.

Inside, the museum presents distinct sections:

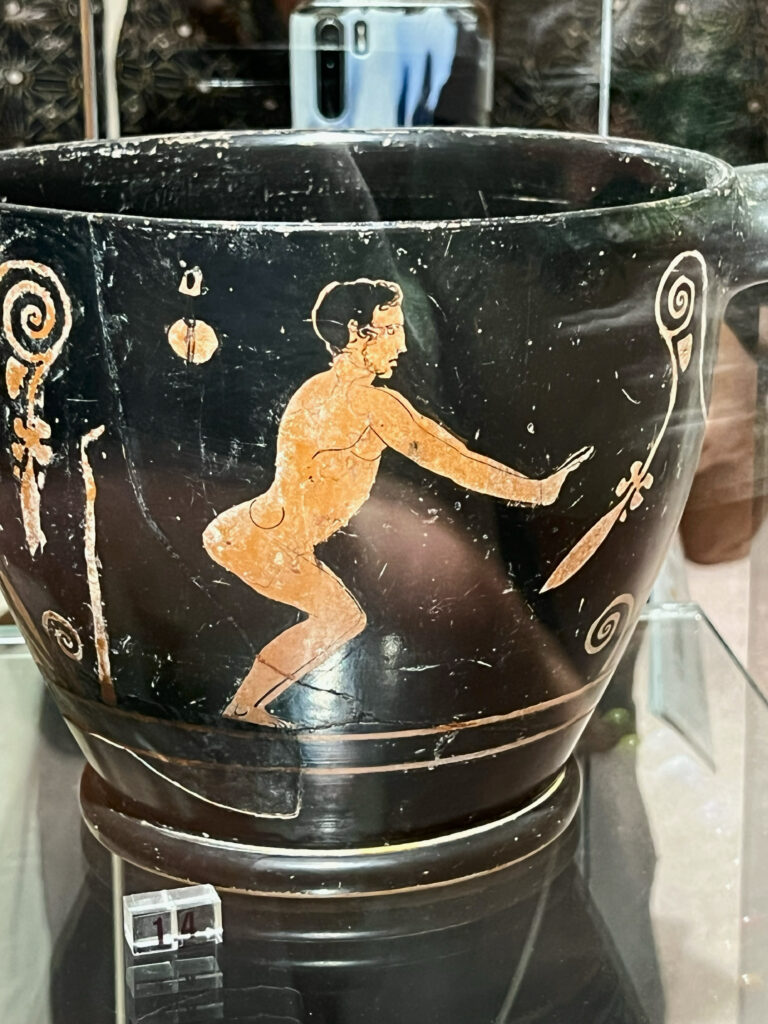

- Antiquities Section: Featuring Messapian trozzella vases, red-figure ceramics, and Gnathian ware.

- Prehistoric Section: Showcasing artefacts from Brindisi’s ancient past, including Attic craters with Dionysian themes.

- Roman Section: Highlighting Brindisi’s strategic importance with coins, statues, and relics like the headless statue of Clodia Anthianilla.

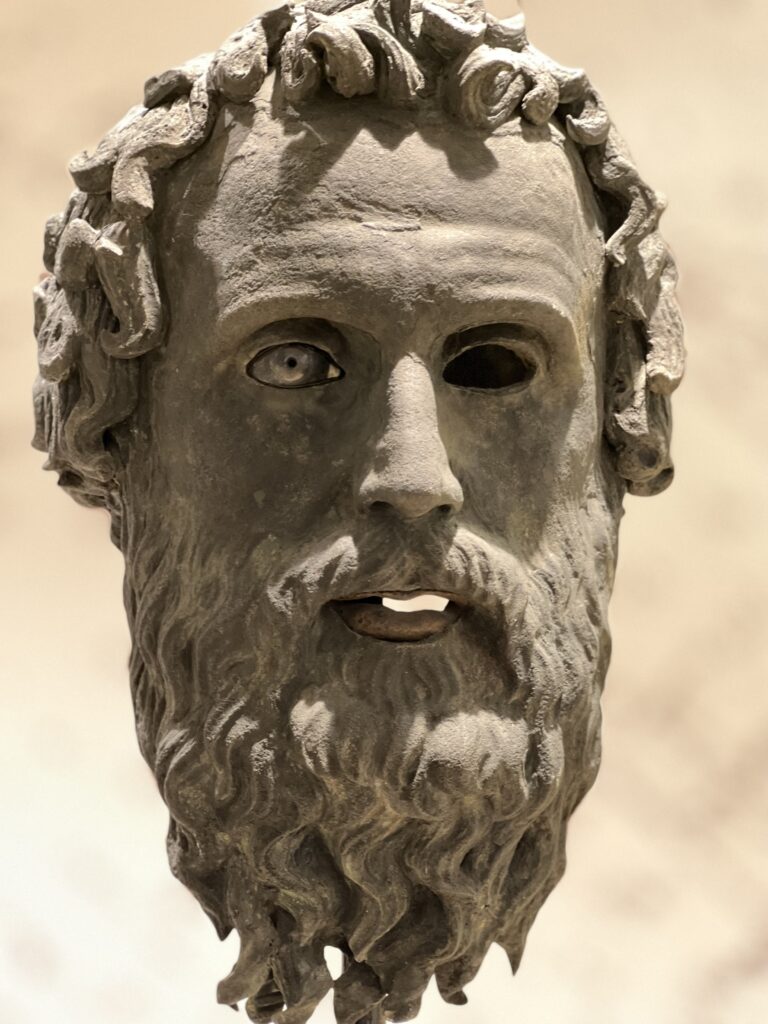

The museum concludes with its Underwater Archaeology Section, displaying amphorae and the bronze statues recovered from Punta del Serrone.

Additionally, the museum is located near the Locanda del Porto, a restaurant overlooking the sea, where you can enjoy delicious dishes after your visit. Its position allows you to savour the view of a deep blue horizon that shines brightly at the end of the street.

The “Francesco Ribezzo” Archaeological Museum | A Deeper Dive

The museum is named after the renowned archaeologist and linguist Francesco Ribezzo (1875–1952). It houses numerous spacious rooms containing fascinating artefacts, including Attic vases and the famous Bronzes of Punta del Serrone, discovered through underwater archaeology. The so-called Portico of the Knights Templar serves as the museum’s entrance, immediately capturing the visitor’s attention. Beneath the portico, a collection of bronze anchor stocks, sculptures, municipal honorary steles, sarcophagi, and architectural elements is displayed, their origins known but their context often unclear.

Beyond the portico, a small courtyard showcases marble altars, funerary inscriptions, and architectural elements of extraordinary beauty, evoking a time long past.

On the ground floor, an expansive room is dedicated to the Antiquities Section, featuring archaeological materials largely from Brindisi. These are organised by category, including ceramics, bronze figurines, votive terracottas, antefixes, lamps, glassware, and coins. This display allows visitors to trace the historical phases that, around the 7th century BCE, led the Iapygian civilisation to evolve into three closely related yet distinct cultures:

- Daunia: Extending from the Gargano to the Vulture, from the Sub-Apennines to the Gulf of Manfredonia, encompassing the entire Tavoliere delle Puglie.

- Peucetia: Corresponding broadly to the modern Metropolitan City of Bari, reaching as far as the Bradano Valley.

- Messapia: Stretching across the entire Salento peninsula to Leuca, the bitter rival of Taranto, a Spartan colony founded in 706 BCE.

Focusing on the Brindisi area and the ancient region of Messapia, the Sala Marzano features remarkable trozzella vases, named after the wheels on their handles, which are typical of the Messapian culture. The room also displays Attic vases, Italic ceramics, and examples of Gnathian pottery—Apulian ceramics from Egnazia in the 3rd century BCE, distinguished by painted decorations. Highlights include Apulian red-figure craters from the 4th century BCE depicting Dionysian scenes.

The first floor is devoted to the Prehistoric Section, exhibiting archaeological findings from excavations in Brindisi and the surrounding province. Among the standout pieces are beautiful examples of red-figure vases, including an Attic column krater by the Hephaestus Painter (5th century BCE) depicting a Dionysian procession near an altar, and an Attic krater featuring Triptolemus in a winged chariot between Demeter and Kore, attributed to the Polygnotus Painter (5th century BCE). These works testify to Brindisi’s ancient trade connections with Eastern ports.

Brindisi’s fame as a port is tied to its unique deer-head shape. The city’s name derives from the Latin Brundisium, itself from the Greek Brentesion, which in turn originates from the Messapian Brention, meaning “deer’s head.”

The second floor explores the history of Roman Brindisi. Before Rome’s arrival, the city was considered the royal capital of the Iapygians. In 333 BCE, Alexander the Molossian, called to aid the Tarantines, respected the city’s ancient history and forged peace agreements with the Messapians. During this period, the Messapian world engaged in peaceful political interactions with Taranto. This alliance with the Macedonian prince Pyrrhus, who came to Taranto’s aid against Rome, helped Brindisi secure a significant role in trade routes to the East. However, in 266 BCE, after the defeat of Pyrrhus and Taranto, Brindisi was conquered by the Romans.

The Roman collection includes Greek and Roman coins, Roman female deities, a trimorphic Hecate statue, and a bas-relief depicting a sacrificial scene. Of particular note is the headless statue of Clodia Anthianilla, a 2nd-century CE Brindisian scholar, accompanied by an inscribed funerary base with a lengthy eulogy.

The museum concludes with a section dedicated to underwater archaeology, displaying numerous amphorae recovered over time along the Brindisi coast, as well as stone and metal anchor stocks. The Bronzes of Punta del Serrone were discovered during a chance dive on 19 July 1992, about two miles north of Brindisi’s harbour entrance. A bronze foot, found 400 metres from the shore at a depth of 16 metres, was the first discovery. Another bronze foot, likely part of an imperial or Byzantine statue, had been retrieved from the same area in 1972 and is now part of the museum’s collection.

Brindisi remains a magical city, brimming with places to discover and captivating stories to tell. Its greatness stems from the curiosity and courage that define humanity itself. The city symbolises an enduring spirit, battling tempests, mythical Gorgons, and Laestrygonians to achieve its splendour.

In antiquity, Brindisi was a cultural hub. In the 1st century BCE, it was home to the patron Lenio Flacco, who transformed his villa on the northern hills of the port into a literary salon, hosting poets like Horace and his dear friend Cicero during his exile in 58 BCE. Virgil also stayed here while writing the Aeneid and passed away in Brindisi in 19 BCE. Today, the city preserves its historical grandeur in its architecture, while its port continues to serve as a gateway for travellers pursuing new dreams and adventures.

May the goddess, Lady of Cyprus, guide you,

along with Helen’s brothers, shining stars,

and the father of the winds close them all,

save the Iapygian breeze, O ship,

entrusted to you, carry Virgil safely,

I beg you, to the land of Attica.

Preserve for me the other half of my soul.

He had oak in his heart

and triple layers of bronze, the man

who first entrusted a fragile craft

to the ferocious sea and did not fear

the rushing Africus, battling the Aquilons,

nor the mournful Hyades, nor the wrath of Notus,

the masterless force of the Adriatic,

able to stir or still the waves at will.

What step of death did he not fear,

who gazed dry-eyed at sea monsters,

the murky deep, and the cursed

Acroceraunian rocks? In vain did a wise god

divide the Ocean from the lands,

rendering them irreconcilable,

when reckless ships still dared

to cross the forbidden waves.

Boldly, mankind, capable of enduring all,

plunges into forbidden sacrilege.

Boldly did the son of Iapetus

bring fire to mortals by deceit.

Since the fire was stolen from the celestial realm,

a host of new afflictions has descended upon the earth,

and slow-moving fate has quickened

the pace of death, once distant.

Daedalus dared the empty air with wings

denied to man.

Hercules’ labour

violated the Acheron.

For humanity, nothing is too difficult;

we madly assault the heavens themselves,

and with our crimes,

we refuse to let Jove lay down

the thunderbolts of his wrath.

This is a translation of the Puglia Guys article originally written in Italian by Riccardo S.